Nestled among the towering peaks of the Karakoram, Baltistan is a land where history, legend, and culture intertwine. Often called the “Little Tibet” of Pakistan, this high-altitude region has been home to ancient kingdoms whose legacy continues to echo through its valleys, fortresses, and folklore. While today Baltistan is a part of Gilgit-Baltistan, its identity has been shaped for centuries by the rise and fall of dynasties, the spread of Buddhism and Islam, and the influence of trade routes that once connected Central Asia with South Asia.

This blog explores the history of Baltistan’s ancient kingdoms—civilizations that flourished in the shadows of giants like K2, Masherbrum, and Nanga Parbat—and how their cultural footprints still define the region today.

Baltistan: A Land of Mountains and Myths

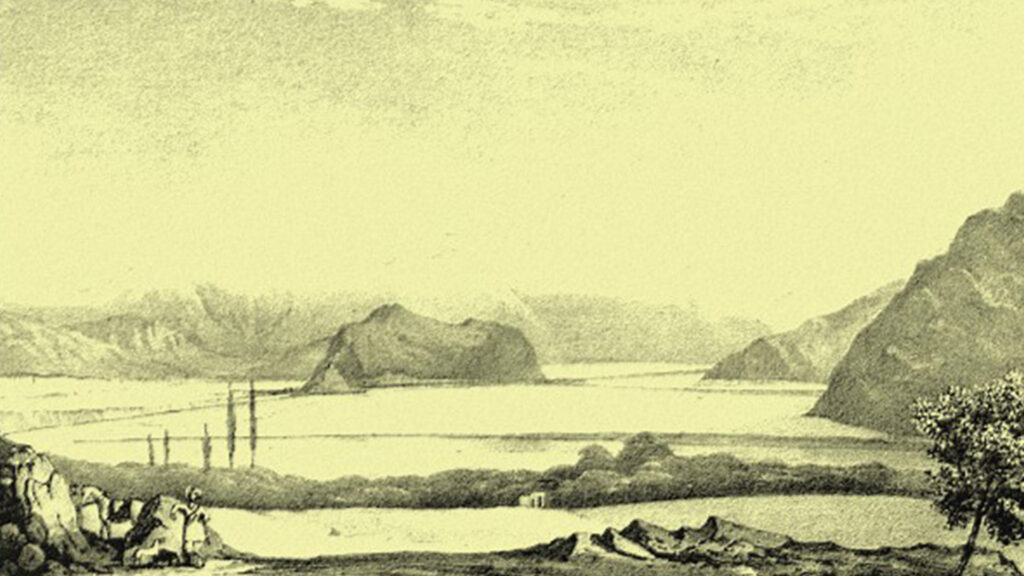

Before delving into history, it is important to understand the geography that shaped Baltistan’s kingdoms. Located at altitudes between 2,500 and 4,500 meters, Baltistan is encircled by the Karakoram Range. Its valleys—Skardu, Shigar, Khaplu, and Rondu—are carved by mighty rivers fed by glaciers, making them both fertile and defensible.

This environment influenced not only how people lived but also how kingdoms were structured. Fortresses were built on high cliffs for protection, while rivers became natural trade routes. The rugged terrain also meant that Baltistan’s polities were relatively isolated, developing unique cultural and political systems.

Early Influences: Buddhism and the Silk Road

Baltistan’s earliest recorded history is tied to the Silk Road. Caravans traveling between Tibet, Ladakh, Kashmir, and Central Asia passed through its valleys, bringing with them trade goods and new ideas. By the 4th century CE, Buddhism had spread into Baltistan, leaving behind enduring marks.

The rock carvings of Skardu, Shigar, and Khaplu depict Buddhas, stupas, and inscriptions in Sanskrit, confirming the region’s Buddhist past. Baltistan’s early rulers likely followed Buddhist traditions, aligning themselves with Tibetan and Kashmiri influences.

The decline of Buddhism in Baltistan began after the 14th century when Islam, introduced by Sufi missionaries, gradually became the dominant faith. Yet, the legacy of Buddhist art and architecture remained embedded in the cultural memory.

The Rise of Local Kingdoms

By the medieval period, Baltistan was home to several petty kingdoms and principalities, each centered on a fertile valley. These included:

- Skardu (the central kingdom) – Skardu was the political heart of Baltistan, ruled by dynasties who built Skardu Fort (Kharpocho) as their stronghold. Its fertile land and access to trade routes made it the most influential kingdom.

- Shigar – Known for its strategic valley, Shigar was an important kingdom with its own rulers who built the iconic Shigar Fort.

- Khaplu – The kingdom of Khaplu lay further east, with strong Tibetan cultural ties. Its rulers constructed the Khaplu Palace, a unique blend of Tibetan, Balti, and Islamic architecture.

- Rondu and other minor principalities – Smaller kingdoms existed in Rondu, Kharmang, and other valleys, often allied or at odds with larger powers.

These kingdoms were frequently engaged in both alliances and rivalries, which shaped the region’s history for centuries.

The Maqpon Dynasty: Baltistan’s Golden Era

The most prominent rulers in Baltistan’s history came from the Maqpon Dynasty, which ruled Skardu and extended influence across the region from the 12th to the 17th century.

Expansion and Power

At its height under Ali Sher Khan Anchan (r. late 16th–early 17th century), the Maqpon Kingdom expanded into Ladakh, Gilgit, and even parts of Tibet. Ali Sher Khan is remembered as a skilled warrior and strategist who brought Baltistan its golden age.

Cultural Contributions

The Maqpon rulers were great patrons of art, architecture, and literature. During their reign:

- The Kharpocho Fort was strengthened as a symbol of Skardu’s power.

- Baltistan’s distinct architectural style emerged, blending Tibetan, Kashmiri, and Islamic influences.

- Balti poetry and folk traditions flourished, leaving behind a rich oral heritage.

Decline

Like many dynasties, internal rivalries and external pressures eventually weakened the Maqpon rulers. By the 18th century, Baltistan’s kingdoms became fragmented and vulnerable to invasions.

Encounters with Tibet and Ladakh

Baltistan’s history cannot be separated from its interactions with Tibet and Ladakh. Cultural, religious, and political ties linked these regions for centuries.

- Marriages between ruling families strengthened alliances. Balti princesses often married Tibetan and Ladakhi kings, forging bonds across the Himalayas.

- Trade and religion flowed through mountain passes, spreading ideas and faiths.

- However, conflicts also erupted. The 17th century saw wars between Baltistan and Ladakh, as both sought control of trade routes and border territories.

These encounters left Baltistan with a unique hybrid culture—Tibetan in its roots, but increasingly Islamic in its worldview.

The Arrival of Islam

The transformation of Baltistan began with the arrival of Sufi saints and Islamic scholars from Kashmir and Central Asia around the 14th century. They introduced Noorbakhshi Sufism, which became deeply rooted in Balti society.

Over time, Shia Islam and Sunni Islam also spread, shaping Baltistan’s cultural and spiritual identity. The conversion was gradual and peaceful, with Sufi missionaries emphasizing inclusivity and tolerance.

This religious shift had profound effects on the kingdoms:

- Buddhist monuments fell into disuse but were often respected as sacred spaces.

- Mosques and khanqahs (Sufi lodges) became centers of learning and culture.

- Local rulers embraced Islam, integrating it into governance and law.

Decline of the Kingdoms and Dogra Rule

By the 19th century, Baltistan’s independent kingdoms had lost much of their power. External forces, particularly the expanding Dogra rulers of Jammu and Kashmir, took advantage of the region’s divisions.

In 1840, the Dogras invaded Baltistan, defeated the local rulers, and annexed the territory into the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir under the Sikh Empire’s successor state. This marked the end of Baltistan’s independent dynasties.

Though stripped of political autonomy, Baltistan retained its unique cultural identity, preserved through oral traditions, architecture, and community practices.

Legacy of the Ancient Kingdom

Architectural Heritage

Baltistan’s forts and palaces remain enduring reminders of its kingdoms:

Skardu Fort (Kharpocho)

Perched high above the Skardu Valley, Skardu Fort, also known as Kharpocho, stands as a testament to the might and authority of the Maqpon rulers. Built in the 16th century, the fort was strategically positioned to oversee the valley and protect the ancient trade routes that once connected Baltistan with Tibet and Central Asia. Today, its weathered stone walls echo with centuries of history, offering visitors not only a glimpse into Baltistan’s royal past but also panoramic views of the Indus River snaking its way through the Karakoram.

Shigar Fort

The Shigar Fort, often called “The Fort on Rock,” is a masterpiece of Balti architecture and resilience. Originally constructed by the Raja of Shigar in the 17th century, it has been meticulously restored and transformed into a heritage hotel by the Aga Khan Cultural Service. This preservation project not only saved the fort from ruin but also brought to life the artistry and skill of Balti craftsmanship. Today, visitors can walk through its wooden balconies and stone courtyards, experiencing a unique blend of history and hospitality amidst the rugged beauty of the Karakoram.

Khaplu Palace

Known as the “Last Tibetan-style palace” in Baltistan, Khaplu Palace is an architectural gem that perfectly captures the fusion of Tibetan and Balti artistry. Built in the mid-19th century by Raja Yabgo, the palace served as the royal residence of the Khaplu rulers and still radiates an air of timeless elegance. With its carved wooden balconies, intricate latticework, and harmonious blend of local stone and timber, Khaplu Palace is a window into a cultural crossroads where Central Asian, Persian, and Himalayan influences converge. Its restoration has turned it into a museum and heritage hotel, allowing visitors to step back in time while enjoying the serene mountain setting of Khaplu Valley.

Chaqchan Mosque

Nestled in the picturesque town of Khaplu, the Chaqchan Mosque is one of the oldest mosques in Baltistan, dating back to the late 14th century. Legend attributes its founding to Syed Ali Hamdani, the Sufi scholar who introduced Islam to the region. What makes the mosque truly remarkable is its architectural blend—combining Tibetan Buddhist elements, Persian motifs, and Islamic design in a way that reflects Baltistan’s layered cultural history. Its wooden beams, carved pillars, and distinct roof structure stand gracefully against the dramatic backdrop of the Karakoram, making it both a spiritual center and a cultural landmark.

Cultural Heritage

- Balti language – A Tibetan dialect enriched with Persian and Urdu influences.

- Music and poetry – Traditional Balti songs celebrate love, nature, and historical battles.

- Festivals – Ancient traditions like the Polo Festival and Navroz trace back to royal patronage.

Historical Memory

Even today, local folklore is filled with tales of Balti kings, queens, and warriors who defended their lands in the shadows of the world’s tallest mountains.

Why Baltistan’s History Matters Today

For travelers and historians alike, Baltistan offers more than scenic beauty. Understanding its kingdoms provides insight into:

- How cultures blend in border regions

- The resilience of mountain communities

- The impact of geography on politics and society

Exploring Baltistan is not just about trekking to K2 Base Camp or visiting glaciers—it is about walking through a land where history still lives in ancient stones and living traditions.

Conclusion

The ancient kingdoms of Baltistan rose, flourished, and eventually fell under the weight of external invasions and internal decline. Yet, their legacy endures in forts that guard valleys, in songs sung by shepherds, and in the very identity of the Balti people.

To visit Baltistan is to step into a world where history is written in both stone and snow—where the shadows of giants, both human and mountain, continue to shape the destiny of this remarkable land.